Once upon a time, we built and managed websites simply by writing HTML source code into a notepad file and uploading our files to a server. In the hazy mists of 2003 - still the era of ‘webmaster’ - many of us were still using products like Microsoft Frontpage and Adobe Dreamweaver to directly edit the code and content of our websites.

But as the internet matured, businesses demanded more flexibility and more sophisticated marketing tools. To connect with and sell to consumers, websites, content and digital channels needed to be easier for businesses and marketers to use and manipulate.

So we introduced abstraction into the process. We put systems and intermediary layers in between us and the raw code. We moved content into databases so that people could edit pages in content management systems, without having to touch the underlying script. We broke our code into many small parts and built logic to determine how different templates and scenarios should behave for different requests and URLs - rather than maintaining files for individual HTML pages.

This changing approach made websites more complicated, and more sophisticated. The web presence of many businesses started to become more reactive and to better answer the needs of consumers - supporting dynamic content, accounts, personalisation, and more diverse experiences. They started to answer the demands of both businesses and consumers much more effectively.

But in many cases, it was too little, too late.

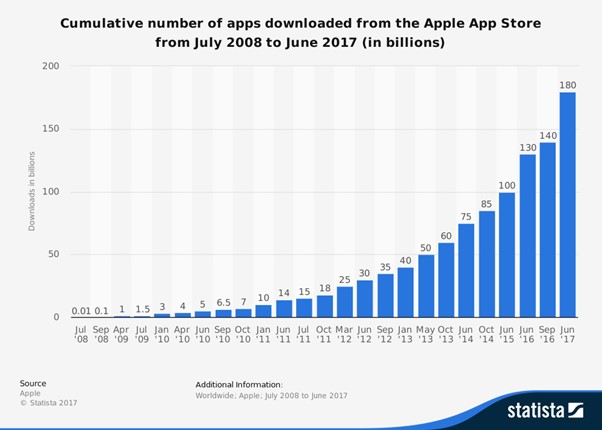

The rise of the app store

By the time 2008 arrived, the mobile app revolution was well underway. Mobile experiences offered a degree of personalisation, fluidity and persistence which many websites had failed to achieve. They frequently offered better experiences than websites, because they knew who I was, saved my data, and offered designed-for-purpose experiences which normal websites struggled to compete with.

Native apps bypassed many of the development challenges around cross-browser support, responsiveness, and interactivity which websites often struggled - and still struggle - with. Whilst web browsers were still clunky and hard to work with, apps allowed for designed-for-purpose experiences which just felt better.

Unsurprisingly, this meant that consumers flocked to, and frequently preferred the kinds of fluid experiences which apps delivered, whilst most websites felt increasingly unresponsive and static in comparison.

jQuery to the rescue

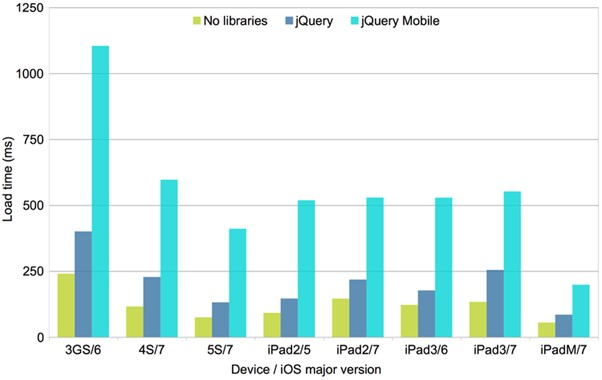

So, it’s no surprise that, around the same time, JavaScript libraries like jQuery began to rise to prominence in the web development community. They offered a quick, easy, and powerful way to overcome cross-browser headaches, and to add interactivity and animation. This empowered even rookie developers to build functionality which felt more ‘app-like’ than the kinds of static websites we were used to seeing at the time.

Hundreds of thousands of websites adopted jQuery and similar libraries in an attempt to try and level the playing field. Overnight, in the web 2.0 revolution, the web became more interactive. The experiences and interactivity which we’d grown to expect from the app ecosystem became much more commonplace.

Except, this power and flexibility came at a cost. jQuery, and solutions like it, have to “bolt on” to websites to add functionality. It takes time and browser resources to load the library, and then more time to process and execute any JavaScript written on top of it. These kinds of libraries also typically ship as a single, large file, which contains the entire library - so even if all I need is a simple function (say, to be able to easily toggle the visibility of an element via a button click), I’ve still got to load the whole thing. That’s a lot of overhead.

So, whilst using jQuery as a sticking plaster went some way to fixing the presentation and interactivity of the web, it made the whole thing much slower. JQuery gained a reputation for allowing rookie developers to make the web even worse and widened the quality/experience distance between websites and the apps they were trying to compete with.

A new approach

It’s for this reason that many developers and organisations went back to the drawing board, and developed new approaches - approaches designed to help build websites which behaved more like apps.

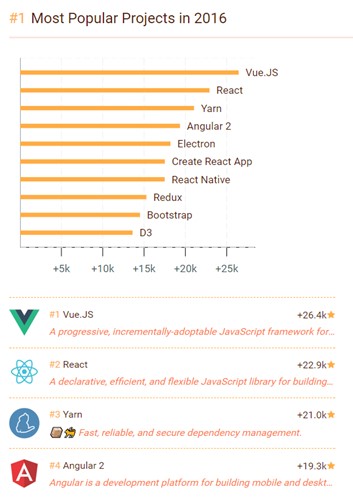

Google’s AngularJs (now simply ‘Angular’) and Facebook’s React frameworks - and more recently VueJS - rose to prominence in this revolution.

These libraries and frameworks are the go-to solutions for developing the kinds of ‘single page apps’ which the SEO community is becoming increasingly familiar with. Their different approach to managing components, page and states makes them well-suited to developing ‘apps as websites’, rather than ‘websites which try to act like apps’.

So, it’s no surprise that these frameworks power some of the world’s biggest and most successful websites - the likes of YouTube and PayPal (AngularJS), or Netflix, The New York Times and Airbnb (React).

And what’s notable about these websites, in particular, is that they feel unarguably more like apps than websites. Where most websites are typically either informational (blogs, affiliate sites and lead generation/brochureware sites) or transactional (ecommerce sites), we can categorise these examples differently - they’re platforms, not just websites. They’re destinations for consumers who want to browse, interact, update, and manage their experiences in a way that doesn’t exist on most websites.

Websites vs Platforms

This dysfunction (where websites are frequently a bit naff, vs platforms, which are generally where consumers want to be and what they want to experience) is one of the biggest drivers behind the kinds of changing consumer behaviours, which we’re seeing more broadly throughout the industry.

Because, brands typically build websites, and they exist to provide a specific function. They have web pages where you can read content, and click on links. They give you the information you want, but only when you seek it out. They enable you to purchase the product or to make an enquiry. These are all singular tasks, which the website is explicitly designed to allow you to complete, on demand. Websites are where you go to do the thing. And, because of these kinds of interactions are typically static, transactional things, websites rarely provide a fluid, dynamic, interactive, personalised process.

The thing about these kinds of on-demand, transactional experiences is that they’re only interesting when I want the thing they offer (or if I can be convinced that I want it). If I’m not interested, there’s no incentive to visit and consume.

With platforms, I visit to discover, without necessarily having a specific agenda in mind. That’s a very different type of experience, with different expectations.

And whilst brands and companies can build platforms which behave in this way, they often struggle to do successfully, as their conflicting objectives of getting you to do the thing (e.g., buy the product) versus allowing you to do your own thing (e.g., look at some cat pictures) compromises the quality of both types of experiences.

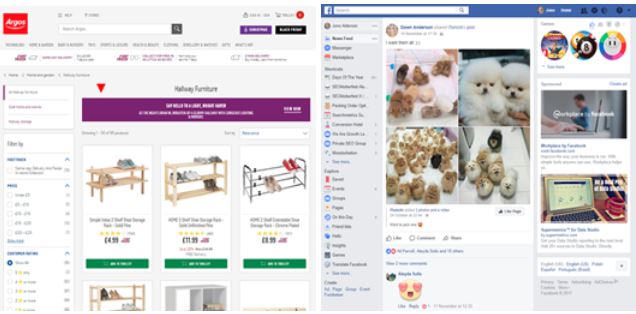

It’s because of this that I’ll never proactively choose to spend hours casually browsing Argos’ furniture catalogue pages - even if they add chat and social elements - whereas I might well choose to spend that time looking at my friends’ cat pictures on Facebook.

Cause, or effect?

You could argue that a large part of this difference is based on the content in those environments. I’m not interacting with Facebook in the same way as I might with Argos; I’m interacting with my peers and their content via Facebook as a medium. But there’s a strong distinction between websites which are built by brands who are trying to get me to do-a-thing, and platforms built by organisations which house the content I want to consume.

And this is just the beginning. The technologies which underpin and enable these kinds of rich, app-like experiences will continue to mature. They’ll provide better experiences in comparison to brand websites. The gap will widen, consumer expectations with continue to rise, and most websites will feel increasingly clunky and transactional in comparison.

Summary...

· The technology which powers the web is changing and maturing. You need to familiarise yourself with how JavaScript frameworks/libraries like React and Vue work if you want to stay at the top of your game.

· The brands who use modern tech to make their websites feel more like apps are winning; app-like websites can be faster, more interactive, more personalised, and better. When cross-device, cross-channel and online/offline experiences seamlessly meld, it’s hard for competitors to take market share.

· Most businesses are still on yesterday’s tech stack, and the gap is widening as technical debt increases.

Cue, advertising

To pull consumers from platforms to websites, we advertise. We run campaigns, invest in Google AdWords and Facebook Ads, strive to rank highly in organic search results, and put billboards on street corners.

We find opportunities to interrupt the media, content and experiences which consumers are engaging with. We buy clicks and eyeballs. To brands, platforms are marketplaces for consumers.

Often, this is the heart of those platforms’ revenue models. They are a magnet for users, and a conduit to/for advertisers. They provide a discovery mechanism for those advertisers, who might otherwise struggle to attract consumers directly.

Grey areas

Of course, the distinction isn’t always that black-and-white. There are grey areas and crossovers. Some industries, like publishing, some affiliate models, and even search engines, often exhibit characteristics of both websites and platforms; consumers may be pulled in multiple directions to fuel a particular advertising model.

And how we might define some brand websites isn’t always clear, either. What about all of the time you’ve invested in content marketing; your rich editorially directed blog posts, and top-of-funnel information which gives advice and support?

Chances are that you’re trying to make part of your website feel and act like a platform - to pull visitors to your resources from places like Google or Facebook. But even if you attract millions of readers and buyers, you’re still paying to acquire this audience (even via, say, ‘free traffic’ like that from organic search or social media) - and they’re still coming from platforms.

At worst, then, your content marketing is just another form of interruption advertising. That’s not to say that your content isn’t necessarily good or useful, but rather, that you’re still stuck paying to move eyeballs from where people want to be, to your product/service. At any minute, that traffic source might dry up. Or it might double in cost. Or the platform you’re buying it from might launch its own, competing solution.

At best, your content marketing is an investment in brand recognition and preference - so that when consumers need your products or services, they remember and trust you, and come to you directly (bypassing, and reducing your brand’s reliance on platforms).

An unrealistic goal?

So the trend and ambition for brands to aspire to become publishers isn’t enough - in the long-term, unless you become a platform, you’ll lose to one, where customers get the content they want, where they already are.

For most businesses, though, that’s a radically unrealistic goal. The technological, logistical and commercial barriers to “becoming a platform” are unsurprisingly insurmountable.

This goes a long way to explaining why the platforms are winning - they control, albeit somewhat indirectly, which brands win and lose, and define the rules of the game.

To attract customers, you must play in their ecosystem - whether it’s Google, Facebook, Twitter, or something else entirely - you must pay to buy clicks and visits from platforms to your website and content.

Summary

· Platforms are marketplaces for consumers. To pull visitors from platforms to websites, businesses spend money (directly or otherwise) to advertise there, to drive clicks and visits to their websites.

· Conventional thinking suggests that brands must gradually transform into publishers, in order to grow earned and owned audiences. But this isn’t enough if they’re still “renting” an audience from platforms (including search engines).

· To get visitors to your website, there’s no way to avoid paying a platform for the privilege - unless you can grow brand recollection and preference sufficiently for consumers to visit you directly, and to bypass the platform(s).

Distributed content

But here’s the good news - you can put your content on their platforms. For free. All of the major players allow you to provide them with your editorial and ‘pull’ content, and they’ll serve it up in situ in a way which avoids all the awkward friction of a user having to leave their comfortable environment.

Facebook Instant Articles, Apple News, and more recently, AMP (Accelerated Mobile Pages), allow users to read, research, and even purchase from a brand without ever leaving the platform they’re browsing.

A better experience

In many cases, these ‘in context’ experiences are better than the brand’s own. They’re certainly faster, generally ‘cleaner’ in design and focus, and less ‘pushy’ when it comes to invasive ads and conversion mechanics.

This raises the question; if your users can find and engage with you in a way which they prefer, from within other platforms, why should they visit your website? Moreso, even, why would platforms afford them the opportunity?

This is a huge shift in online behaviour, with huge implications. Brands are ceding control of ‘their’ customer experiences and content, sacrificing ownership for in-platform discoverability.

It’s important that we don’t underestimate the importance of this shift in the ownership of content, else we risk disastrous results.

More than just new channels

Many brands have approached AMP and similar frameworks simply as new channels to add into their marketing mixes; new storefronts which just require extra thinking and resource to optimise and maintain.

But there’s a deeper change underway. This the tip of the iceberg, of a revolution from an owned media model to a distributed content model; a shift from websites publishing editorial and ‘pull’ content to attract consumers, to those consumers much more commonly encountering and engaging with that content in other environments.

And that stretches far beyond Google, Facebook and Apple. Your content, or your competitors’, is increasingly being discovered and consumed - and purchase decisions are being made - in environments you don’t control.

Your ‘pull’ content is being shared, syndicated into and read in WeChat, Slack, and WhatsApp. Your products and services are being compared and purchased on your AMP pages and in third-party marketplaces.

Even if you’re not actively enabling or encouraging this kind of behaviour, your audiences are sharing links, your products are being compared, and people considering your solutions - or not - where you can’t easily track or influence them with ads, special offers or retargeting.

It’s going to get harder

And that’s just today’s platforms. The fragmentation, volume and velocity of these environments continues to increase. Tomorrow, there will be dozens of new places where your audience are, where they choose to consider your products and services on their own terms - without them ever visiting your website.

So if your site doesn’t offer users something distinctly valuable - enough so that they’re willing to visit it directly, rather than consuming what you offer through their preferred platforms - your traffic volumes are going to plummet. They’ll engage with you on their own terms, via platforms which give them better experiences, and less of your pesky and distracting advertising.

Source: DesArt Lab

And this trend will continue to grow. At the extreme edge of this revolution, apps like Pocket and Flipboard allow the consumer to own the entire content experience, and to create their own tailored content platforms - completely bypassing not only your website but also, critically, any advertising or conversion nudge mechanics which you might utilise to move users through a buying cycle.

You’re no longer in control, because it’s all happening out there.

Summary

· There’s a growing set of tools and options which allow you to place your content and messaging in situ on platforms.

· Many brands have approached these new content outlets as new or additional marketing channels - but this overlooks the broader trend of distributed content, where the thing they say/do/sell is increasingly consumed elsewhere.

· As more content, products and brand interactions happen on platforms, your website needs to provide a distinct reason for people to visit it.

A new marketing model

We can’t treat these apps and platforms like new or additional marketing channels. This revolution isn’t one of new or increased numbers of media outlets where I can advertise at consumers, but rather, a deeper shift in how and where content (and, as part of that, advertising) is consumed.

To compete effectively in this new landscape, we need to change the way we think about the relationship between our marketing and our audiences.

The objective can no longer be to attract consumers to your website, in the hopes of converting some small percentage of those visitors to sale or action. At least, not if you want to grow to reach new audiences, or to break free of renting or paying for visitors from platforms.

Instead, knowing that purchase decisions happen in other environments, the roles of content and brand websites need to shift away from conversion, and towards positively influencing preference and brand recall.

Rather than my content being part of a funnel to pull visitors from platforms to my website and attempt to get them to buy, it needs to become a vehicle to grow my brand’s reach into the environments where my audiences are already consuming content.

Rather than my website being the final destination in a purchase journey, it needs to become a hub for the stories I want to tell, and the values I want to showcase - feeding content and conversations which are happening out there, outside of my control.

To a generation of digital marketers who obsess about conversion rates and clicks, this might sound radical, and perhaps even dangerously naive.

But the world’s most successful brands have long understood that this model works, and have embraced this kind of thinking for decades. Brands like Ferrari, Lego, Diageo, P&G, Johnson & Johnson and many others market exactly like this precisely because they understand that they don’t control the conversation.

Take a look at P&G

Chances are, Procter & Gamble manufactured most of the cleaning and sanitary products in your home, and have done for decades.

Their reach, scale, and years of successful advertising and marketing have helped them to develop a deep understanding of how consumers choose products and build brand preference.

But they’re an analogue business, rooted in TV adverts and supermarket shelving.

So when the digital marketing revolution began, they were slow to react and adapt. On the surface, parts of their web presence still look unsophisticated; like they’ve just ported their analogue marketing models to the web.

Even today, very few of P&Gs many hundreds of product websites actively try to be a competitive ecommerce destination. But that’s not because they’re unsophisticated; rather, it’s because they’re applying a deep understanding of how consumers behave to their digital strategies.

They know that conversations and purchase decisions are heavily influenced and happen outside of the controlled environment of their sites, both online and offline. In many cases, when they know that they can’t own the conversation, it’s more sensible for them to try and influence online than to sell online.

Because if all their websites do is try to sell you cleaning products, you’ve no reason to actively choose to visit, and no reason to stay beyond transacting. More impactfully, none of their content organically permeates the platforms where consumers spend time - and as more and more closed-loop experiences exist entirely in platforms, that means missing out.

And whilst they could buy their way into some of those spaces, the cost of advertising into Facebook, Instagram and other environments will become increasingly expensive when it’s not amplified or supported by an established organic reach.

So P&G’s websites, content and messaging often focus more on their ethos, values, and storytelling than they do on selling.

By producing content which educates, supports, inspires or otherwise helps consumers more broadly, that content is more likely to spread throughout a myriad of platforms and formats. It’s more likely to be read, watched, and interacted with.

Then, when the consumer encounters their brand in a context or a platform they don’t control, they have a much higher brand recall and preference - and that means a chance of a step towards a purchase, and a chance for a P&G product to win in the consideration set.

That’s not to say that P&G are perfect; many parts of their business cling onto yesterday’s behaviours despite shifting trends, and they’re hurting because of it. But all the evidence suggests that they understand where they’ve made mistakes, and they’re making changes to enable a renewed focus on effective consumer marketing.

You have to influence earlier

Just because your conversion mechanism lives online and is part of your website, that doesn’t necessarily mean that it needs to be the exclusive focus of your site.

There’s a common assumption, and often a drive from senior stakeholders, that brand websites must operate as machines designed solely to convert visits into sales. Often, that means that any educational, supportive or branding content and functions are percieved as distractions from this focus, and a detriment to conversion rates.

But conversion is frequently only the end of a journey which contains multiple touch points - many of which aren’t on your website or in your control. If all your website does it optimise for conversion, it does so at the expense of conversations which may have influenced future purchase decisions. You’re optimising inwards, rather than outwards.

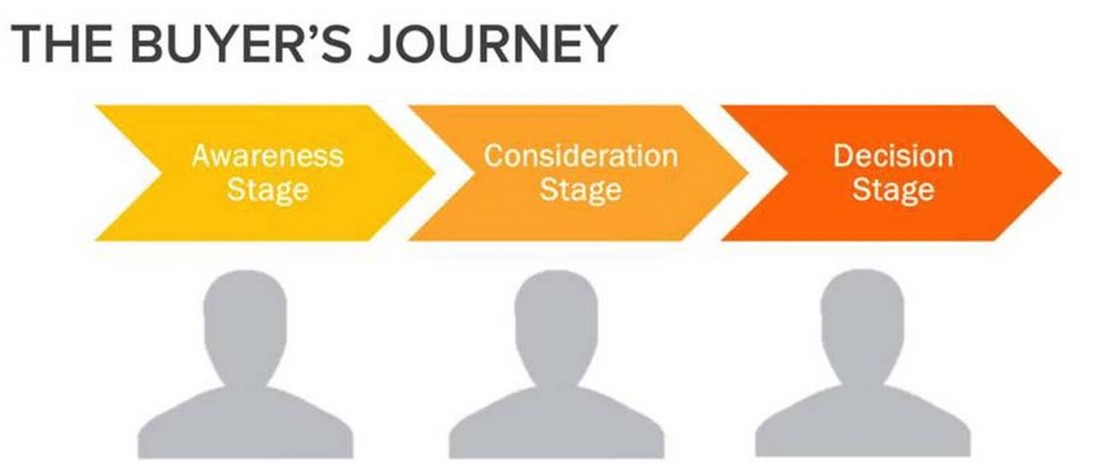

Our obsession with the final stage of the buying cycle means we often omit or overlook critical earlier phases, where consumers are building consideration sets, ruling brands in or out, and forming opinions and preferences.

I’ve talked previously about how the experiences that consumers have early in their research processes influence what happens later; determining which brands make it to the final consideration phases. I described a personal experience, which started with a Google search for “fuzzy sound on tv”, in an attempt to self-diagnose a fault with a television. Six months later, that journey led to a purchase - informed by multiple searches, conversations, research phases, and brand interactions.

I noted that, in many of the early stages of my research, big brands were noteably absent from search results and social media. They missed an opportunity to build brand recall and preference. In some cases, they ruled themselves entirely out of the buying cycle, where they failed to address reputation issues, or failed to provide content which answered my questions as a potential buyer.

If those brands had focused less on the end of the conversion journey, and spent more time proving that they’re reputable and a good fit earlier on, my consideration set might have looked very different.

And in this new revolution, not only will those experiences happen completely outside of the control of those brands (on Ebay, Amazon, Facebook and WhatsApp), but they’ll be eclipsed by the conversations which do happen in those environments.

The product research journey which might once have lead me to an ecommerce website, a blog post, or even an offline store visit is less likely to happen. More and more of my research and decision-making process is unfolding within platforms, and my purchase decisions will be influenced by the content I consume there.

I’ll engage with the brands who’re present in my streams - those who provide useful, supportive content - and buy from them, when I’m ready, without ever leaving that environment.

To compete for attention and business, brands must consider the role their website and their content plays in helping audiences who aren’t yet at the point of conversion. They’ll either need to provide increasingly compelling reasons for people to visit and engage with their websites directly, or they’ll need to completely embrace a distributed content model - and accept that they’re tethered to advertising and syndicating content within platforms, rather than on their own websites.

You must influence from the outside-in

This exclusive focus on conversions, sometimes at the expense of building brand trust and familiarity, is largely driven by how easily measurable and attributable digital channels can be. It’s easy to manage a business when you can spend money to drive visits, and you can measure and forecast the commercial outcomes of those visits.

But that measurability only exists at the end of the funnel, when - or if - the visitor has arrived at your website, or engaged with your ads.

That limits the kind of marketing and advertising that you can do, and optimises for attracting visits from people who are already ready to buy. It actively optimises away from people who aren’t ready yet.

Source: Marketing Directo

Consider that, as more experiences occur on platforms and are fragmented across many environments, fewer and fewer people will want or need to visit your website. That’ll make it harder to directly measure and report on their behaviour. The people who reach your measurable platforms will be a minority in your potential market; traffic you’ve bought or rented from platforms, or those who’ve come direct due to brand recall and preference.

Critically, you won’t be able to measure the people you aren’t reaching - the people who never entered the buying cycle, never searched on Google, and never viewed your display adverts. These are the people who are happily consuming content and making purchase decisions from within their platforms of choice. They’ll never hit your radar.

To reach them, you’ll need to sacrifice ownership of the journey, and to shift your focus from conversion to relationship. You’ll need to change the objectives of your marketing and advertising from enticing clicks back to your website, to engaging, conversing with and converting audiences in situ. Frequently, that’ll be a very different type of messaging and content than we’re used to producing.

Conventional business logic suggests that you shouldn’t build value on rented platforms - there’s always a risk that external factors can destroy your foundations. But what happens when there are only rented platforms, and they’re transient, temporal things? Where do you build your equity?

The answer is simple - you build it in your consumers’ minds. You think outwards, not inwards, and you invest in providing distributed content and experiences which positively influence the marketplace.

You stop obsessing about how big you can build your medieval castle of a website, and you go out and spend time in the fields, with the peasants.

Jono Alderson

He is a well-known and respected figure in the digital marketing industry and, after few years working at LinkDex and Distilled, is now SEO Expert at Yoast BV. He's previously worked with startups, household brands, FTSE 100 companies and global businesses, working on everything from 'big picture' strategic decisions to the nitty-gritty tactical level detail.

You can follow him on Twitter and LinkedIn.